The KZ-Gedenkstätte Dachau is a memorial at the first concentration camp opened by the Nazis near Munich in 1933.

KZ Dachau, the first concentration camp opened by the Nazis in 1933, is now a memorial center for victims of National Socialism. Between March 22, 1933, and liberation by the US Army on April 29, 1945, well over 200,000 people moved through Dachau (and many more through subsidiary camps) with 32,000 recorded deaths. Visiting the KZ-Gedenkstätte is very interesting but emotionally draining – it is not recommended for children. Guided tours are available from Munich or a few times per day from the information center — book when buying tickets, as tour reservations are not currently possible and group size is limited.

Visit Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial near Munich

This short description of the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site basically follows the map issued free by the Visitors Center. KZ is the abbreviation for Konzentrationslager, German for concentration camp, while Gedenkstätte means memorial.

The modern Visitors Center right at the KZ-Gedenkstätte bus stop and the main entrance to the memorial complex is a good first stop to pick up a free map of the site. Audio guides may be rented here while a bookshop has a large range of books in German, English, and other languages. Guided tours take around 2.5 hours and currently, reservations are not possible.

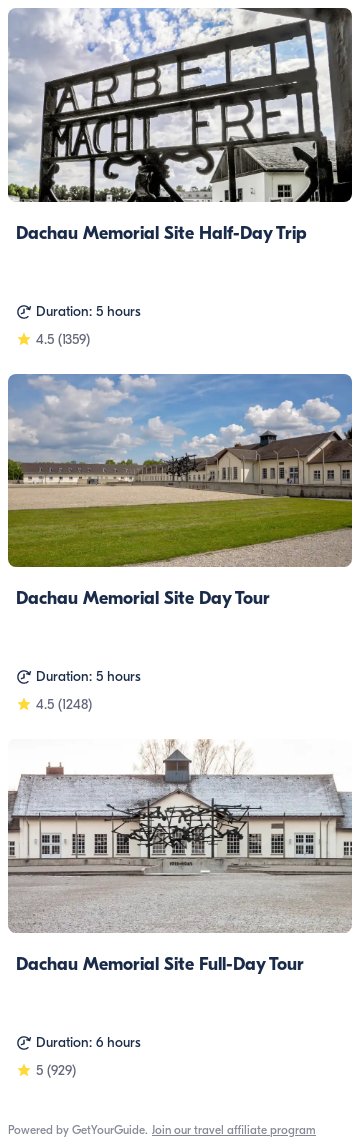

Arbeit Macht Frei Gate

The main entrance to the concentration camp is via the Jourhaus (SS offices) where the original “Arbeit Macht Frei” gate is. (Similar signs were used at many other concentration camps including Sachsenhausen near Berlin and possibly most famously at Auschwitz.)

“Arbeit macht frei” is usually translated as “work sets you free” or very literally “work makes free”. Prior to the Second World War, prisoners were often released from Dachau but never due to hard work.

Exhibition and Barracks at Dachau

The main exhibition is in the large former maintenance buildings. Reading all the information here will take more than three hours alone but no one can deal with such information (and emotional) overload in a single day. Descriptions (in English and German) and photos are graphic and not sanitized making the museum unsuitable for children under at least twelve years old.

A 22-minute movie is shown several times per day in the cinema in the center of the building complex.

Parallel to the main building is the “bunker” or former camp prison (and torture center). Exit through the door at the end of the permanent exhibition or simply walk around the outside.

Two barracks have been reconstructed across from the roll call area. (The camp was used as a prisoner camp immediately after the Second World War and later as a refugee center for Germans made homeless in areas ceded to other nations after the war. During this period the original barracks were altered or destroyed.)

In the barracks are three interiors showing how sleeping conditions deteriorated in the camp as the numbers often increased without expanding the size of existing buildings.

It is a long walk, and on a quiet day surreally peaceful, from the reconstructed barracks along a tree-lined avenue past the foundation of other barracks to the back of the original camp. Here, are Jewish, Catholic, Protestant, and Russian Orthodox chapels and memorials.

Crematorium and Deaths at Dachau

More disturbing is the Crematorium area with two original crematoriums. Officially, the gas chamber – which visitors may freely enter – was never used but few would accept that it was never tested. Dachau was not an extermination camp such as Auschwitz – large groups of Jewish and sick prisoners were sent elsewhere to be executed – but death from overwork, disease, malnourishment, and downright murder was common.

Officially, 32,000 deaths were recorded at Dachau – “only” 500 prior to 1939. However, many deaths were systematically not officially registered. The total number of people who died at Dachau is generally estimated at around 43,000.

Further related sites in Dachau include the Path of Remembrance between Dachau station and the camp, the plantation where prisoners were forced to do hard labor, the shooting range where many Soviet soldiers were murdered, a mass grave memorial site, and the graveyard where many prisoners who died after liberation were buried.

Visitor Information for Dachau Concentration Camp

The memorial grounds are open daily from 9 am to 5 pm. It is currently only closed on December 24. Admission is free — no tickets or time-slot reservations are required.

The memorial site and buildings are almost fully accessible to wheelchair users.

Official guided tours in English are available a few times per day while audio guides offer an alternative if desired – the descriptions in German and English are very comprehensive. Guided tours may also be arranged from Munich to include transportation.

Getting to Dachau Concentration Camp is easy on public transportation from downtown München or Munich Airport (MUC). If traveling from Munich, visiting Dachau is a half-day excursion – expected to spend two to three hours at the camp plus around an hour for transportation each way.