Visit the Palazzo Massimo Roman National Museum in Rome to see top sculptures, portraits, bronzes, mosaics, and even frescoes from antiquity.

The Palazzo Massimo has one of the finest collections of busts and sculptures from antiquity in Rome. As the main venue of the Roman National Museum (Museo Nazionale Romano), the best archaeological finds in Rome since 1870 are on display here. Famous works include two Greek bronzes (Boxer at Rest and Hellenistic Prince), a Greek marble Wounded Niobid, two Roman marble discus throwers, Crouching Aphrodite, a huge collection of busts, and fine Roman copies of Greek originals. The museum also has a large and varied collection of mosaics, as well as very rare, and surprisingly colorful, frescoes from Roman residences. Save with Roman National Museum combination tickets.

Permanent Displays in the Palazzo Massimo in Rome

The Palazzo Massimo alle Terme near Termini Station in Rome is the largest and best-known museum of the Museo Nazionale Romano (Roman National Museum). Although the Massimo is home to the best sculptures, reliefs, frescos, mosaics, stuccoes, and sarcophagi excavated in the larger Rome area since 1870, it is rarely very busy and a pleasure to visit. (Many further sculptures from antiquity that were rediscovered earlier are on display in the Palazzo Altemps near the Pantheon (which is no longer free!) and in the Capitoline Museum.

The museum may be explored in any order but the suggested route is a good option and visits the following themes and collections:

- Portrait Gallery (sculptures and busts rather than paintings) — although the Imperial family is very well represented, images are not only of the rich and famous.

- Greek Originals — marble sculptures and two fantastic, rare large bronzes that the Romans brought back from Greece.

- Copies of Greek sculptures — several very famous copies of ideal sculptures and Roman derivatives.

- Romans sculptures, reliefs, and sarcophagi.

- Mosaics — an exceptional collection of mosaics from the Republican era to the end of the empire.

- Frescoes — wall paintings from several villas reconstructed to display them as if in the original rooms and settings.

- Coins and Jewelry — an excellent collection of especially coins in the basement of the museum. (The collection may still be closed for renovation.)

Portraits Gallery

The portraits gallery gives an overview of how the portrayal of individuals developed from the earliest Greek sculptures to the end of the Roman Empire. Portraits here refer to sculptures, especially busts and heads, rather than paintings or drawings.

The imperial family, especially the Julio-Claudian dynasty, is very well represented, as are other famous people such as Alexander the Great and Greek philosophers. However, many busts are from ordinary people, as are many images on sarcophagi or similar funerary reliefs to remember faces after death. Depictions range from the Greek idealized face to the more realistic Roman images.

Notable works include the portrayal of Augustus as Pontifex Maximus, Germanicus Julius Caesar, Caligula, Hadrian, Antinous, Julia Domna, Marcus Aurelius, and a nude Antoninus Pius.

Greek Original Sculptures and Statues

The original Greek statues in the Palazzo Massimo are in many ways the most impressive in the museum and only in part because these are so rare. Many were transported to Rome after the conquest of Greece and before the Romans started to copy Greek works en masse.

Greek Bronze Sculptures in the Massimo in Rome

Two Hellenic bronzes, found in 1885 on the Quirinal Hill near the Baths of Constantine, are among the most famous sculptures not only in this museum but in all of Rome:

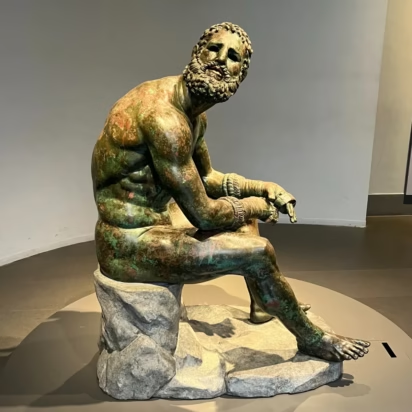

Bronze Statue of a Boxer at Rest

The Boxer at Rest (Pugilatore in riposo), also known as the Terme Boxer, Seated Boxer, Defeated Boxer, or Boxer of the Quirinal, is a highly realistic portrayal of a seated boxer after the fight. Injuries on his body (and nose) are obvious — red copper was used to highlight wounds and even blood dropping down. It was cast using the lost-wax process with the eight pieces soldered together.

The statue is a masterpiece of Hellenistic athletic professionalism, with a top-heavy over-muscled torso and scarred and bruised face, his penis bound by a kynodesme, cauliflower ears, a broken nose, and a mouth suggesting broken teeth. The Boxer is dated to the late Hellenistic period (2nd to 1st century BC) and was probably inspired by the works of Lysippos.

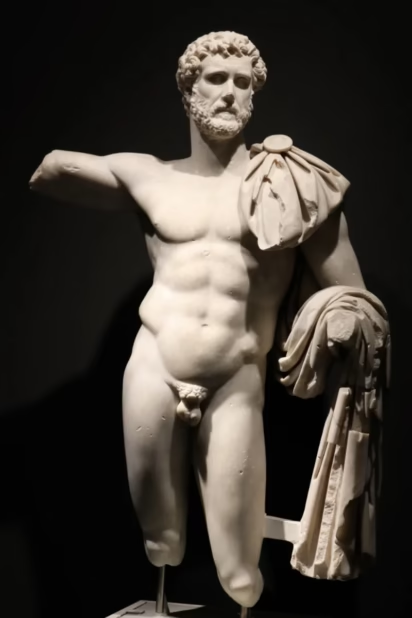

Bronze Statue of a Hellenistic Prince

The Hellenistic Prince, Seleucid Prince, or Terme Ruler (Statua ritratto, cd. Principe ellenistico) is a robust, standing male portrayed in heroic nudity — a pose reserved for a sovereign or very senior military leader. This Greek bronze measuring 204 cm tall was cast using the lost-wax process. The muscular naked body leans on a spear (modern replacement) in a pose similar to works by Lysippos of Alexander the Great and Heracles. The young face has a beard scratched into the surface and the eye sockets were originally filled with white marble. Debate continues about its age and purpose: as a Hellenistic prince it is considered to date from the 3rd to 2nd century BC, as a victorious Roman general it is at least a century newer.

Greek Marble Sculptures in the Massimo in Rome

A few marble sculptures in the museum are Greek originals. Particularly famous is the Wounded Niobid (Niobide ferita)– a young woman trying to pull a (no longer existent) copper arrow from her back. It was part of a larger group that probably included her mother, sisters, and brothers being attacked by Apollo and Artemis. It dates from around 440-430 BC.

On a circular base are depicted three Maenads, priestesses of the god Dionysus, who under the influence of the divine madness, abandon themselves to bare-footed dancing. Production of Greek workshops of the second half of the 1st century B.C

Roman Sculptures in the Palazzo Massimo in Rome

Roman sculptures were often copies of Greek originals depicting gods, myths, and athletes but increasingly also portrayals of the ruling classes and funerary statues. Later Roman works were often far more realistic than earlier Greek portrayals of the ideal face and body.

Roman marble copies of Greek sculptures include two fine examples of the discus thrower — the complete Lancellotti Discobolus and the Discobolus of Castelporziona that has lost his head, an arm, and lower limbs. These copies are based on the original bronze by Myron, ca. 450 BC. Despite the difficulty of reproducing the discus thrower in marble, many copies were made during the Roman era with the two on display dating from the Hadrianic period (AD 117-138).

One of the earliest Roman marbles on display is the so-called Tivoli General. This Greek-style marble produced around 90 to 70 BC portrays an elderly person with a young, nude body. It was probably a high-ranking soldier leaning on a staff as a “heroic nudity” (effigies achilleae) similar to the bronze Hellenistic Prince.

Various sculptures of Aphrodite (Afrodite / Venus) are on display in the museum. Two Roman copies of the Crouching Venus confirm that even the most beautiful goddess had to deal with love handles — the Greek original was from the mid-3rd century BC but many Roman copies survived especially the Hadrianic period in the 2nd century AD. The complete Aphrodite of Menophantos is a Venus Pudica of the Capitoline type signed by Menophantos, first century BC.

Hermaphroditus, the two-sexed child of Aphrodite and Hermes (Venus and Mercury), was according to Ovid a remarkably handsome boy. He rejected the advances of the naiad Salmacis but her prayers to be united with him forever were answered when their bodies merged into one. Greek mythology could be rough.

The Sleeping Hermaphroditus in Palazzo Massimo is one of several Roman marble copies of the Greek original to have survived. A further one is in the Villa Borghese Gallery although the more famous Borghese-Hermaphroditus on a Bernini-carved mattress is now in the Louvre.

Roman Sarcophagi in the Palazzo Massimo in Rome

The Palazzo Massimo has several sarcophagi on display. A remarkably finely carved and well-preserved one is the Portonaccio Sarcophagus from around AD 180. It depicts a symbolic battle between Roman horsemen and barbarians on two levels. The face of the general at the center is unfinished hinting at the sarcophagus being produced on speculation. On the frieze, the wife is depicted as exercising her domestic virtues including educating the children while the husband receives the submission of his enemies. Similar scenes are depicted on the Great Ludovici Sarcophagus in the Palazzo Altemps. Other sarcophagi have themes of Christianity.

Roman Bronze Sculptures in the Massimo in Rome

Roman bronzes are very rare too — through the centuries many were simply melted down with the metal repurposed — but the Palazzo Massimo has a few fine examples on display:

Dionysus (Dioniso) is portrayed as a large male nude standing with a thyrus and adorned with vine shoots. His white limestone eyes were preserved while his mouth and nipples were produced using the copper damascening technique. It dates from the Hadrianic Period (AD 117-138). (Fine further Roman bronzes including Boy Picking a Thorn and the original Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius are in the Capitoline Museum.)

Numerous bronze decorations survived from a ceremonial ship that Caligula built on Lake Nemi as part of a Diana cult. The wooden boats were destroyed by fire during the Second World War but several amazing bronze elements survived, including a head of Medusa, several screen elements, beam heads with lion or wolf motives, and crossbeams with forearms and hands.

Mosaics in Palazzo Massimo

The Massimo has a large collection of mosaics that covers the entire Roman Empire era from the Republican period to the fall of the empire. These are on display on the top floor of the museum.

Also on display are several opus sectile decorations of thin sheets of marble, stones, and colored glass sheets used to form wall and floor inlay decorations.

Roman Frescoes in the Roman National Museum

The museum is also famous for the Roman frescoes and a few stuccoes that were taken mostly from residential houses in or near Rome and rebuilt inside the museum to scale so visitors may enter some rooms and see the frescoes as they were originally intended to be seen. Trompe-l’oeil perspectives and fantasy landscapes were very popular.

Villa Farnesina was decorated in the early Imperial Age. Here many architectural elements such as fake columns and friezes were painted on the walls to frame fresco paintings and bas reliefs.

The Villa di Livia had a lush garden painting to decorate the underground dining room of the summer house of Livia, the wife of Emperor Augustus. Details include flowering plants, fruit, pomegranates bursting open, birds, and trees swaying in the wind to create the perception of being outdoors.

The Large Columbarium in the Villa Doria Pamphili — 1st century AD burial niches for cinerary urns and inscriptions with the names of the dead. Some of the drawings depict arguments between Pygmies and hippos — in Roman eyes, these two never got along. This theme is also very prominent in Pompeii and in two Nile mosaics on the same floor in the museum.

Visitor Information for the Palazzo Massimo in Rome

Tickets for the Palazzo Massimo in Rome

Admission to the Palazzo Massimo in Rome is included in the four National Roman Museum sites combination ticket, which is €12 and good value for adults, €8 for EU citizens 18 to 25 (may do better on single admissions), and free for those under 18. The other sites are the Palazzo Altemps with another fantastic sculpture collection near the Pantheon (which is no longer free!), the nearby Baths of Diocletian, and Crypta Balbi (which is currently closed but not giving any discount!).

The Palazzo Massimo (or any of the other museum venues) may also be seen on a single ticket — €8 (€2 for EU youth, which makes it better value than the combination ticket).

The combination ticket is valid for a week and a small surcharge (€3-5) is payable if a museum has a special exhibition. If bought at one of the smaller museums, it is possible to enter the Palazzo Massimo directly without passing by the ticket desk.

Tickets may also be bought online in advance — €2 surcharge — but it is frankly rarely really necessary.

Opening Hours and Location of the Massimo

The Palazzo Massimo is open Tuesday to Sunday from 9:30 to 19:00 (final admission at 18:00).

The Palazzo Massimo, Largo di Villa Peretti 2, Roma, is basically across the road from the Roma Termini station — exiting at Repubblica may be easier when using the metro.

Further sights in the immediate vicinity include the Baths of Diocletian Museum, the Michelangelo-designed Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri church, and the Santa Maria della Vittoria with Bernini’s Ecstacy of Santa Teresa sculpture.