The Nebra sky disc (Himmelscheibe von Nebra), the oldest concrete depiction of the cosmos, is the top sight to see in the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle, Germany.

The State Museum of Prehistory Halle (Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte Halle) in Saxony-Anhalt is one of the oldest and most important archaeological museums in Germany. It is mostly famous for the Sky Disk of Nebra, which is the oldest concrete depiction of cosmic phenomena worldwide, but it has an easy to enjoy exhibition on humanity in central Germany from the stone age to the Roman period.

State Museum of Prehistory Halle in Saxony-Anhalt

The State Museum of Prehistory Halle (Landesmuseum for Vorgeschichte Halle) is the main archaeological museum in the state of Saxony-Anhalt in central Germany. Its permanent collection includes over 16 million items making it one of the largest and most important museums of its kind in Europe. It was established in 1819 and has been in the purposely built museum since 1918.

The museum has several significant and unique items, but it is the Himmelscheibe von Nebra, the oldest concrete depiction of the cosmos dating from c. 1800 BC, that attracts visitors from all over the world.

Other important items include the 370,000-year-old skeletal remains of Homo erectus, an 80,000-year-old Neanderthal fingerprint, and nobility graves from Leubingen (1942 BC) and Profen (40-65 AD) with golden burial objects.

Permanent Exhibition in the Prehistory Museum Halle

The top floor of the museum covers mostly the stone age with the early bronze age and the sky disc of Nebra. One floor lower is the late bronze, early iron age and a small exhibition on the Roman period.

The exhibition rooms of the museum are mostly organized chronologically, as could be expected from a state and research museum, and grouped in six major themes:

- Mental Power / Geisteskraft

- Human Succession / Menschenwechsel

- Living Changes / Lebenswandel

- Passion for Bronze / Bronzerausch, including the Sky Disc of Nebra

- Born in Fire / Glutgeboren

- The Discovery of the Germans / Die Erfindung der Germanen

Sky Disc of Nebra in Halle

The sky disc of Nebra (die Himmelscheibe von Nebra) is by far the most significant exhibit in the museum and the main draw for most foreign visitors. It was discovered by treasure hunters in 1999 at Nebra, not far from Halle, just in time to be classified as one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. It was included in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 2013.

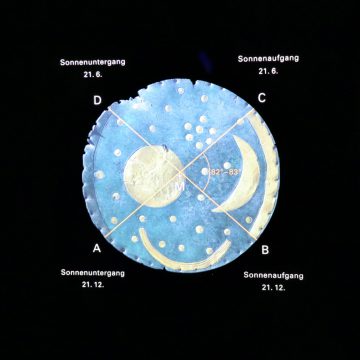

The sky disc was created around 3600-3800 years ago in central Germany and is considered the oldest depiction in the world of cosmic phenomena. It shows an extraordinary understanding of astronomical phenomena but was probably used for religious purposes too.

The Nebra Sky Disc is a circular bronze disc of 31 – 32 cm with a thickness of between 4.5 mm in the center to 1.5 mm on the edge. It weights 2050 grams.

The original brownish aubergine disc now has a green patina but the golden inlays maintained their color. These consist of a full moon (or sun), a crescent moon, 37 stars, two horizon arcs (one lost), and a golden arch as a stylized ship. The perimeter of the disc is perforated by 38 holes. The reverse of the disc is plain.

Origins of the Sky Disc of Nebra

Current research indicates that the disc was produced or altered in five phases, as is especially clear from the different composition and origin of the gold:

- Phase 1: The round bronze disc including 32 stars, the full moon and crescent moon were produced locally probably around 1800 BC. The group of seven stars — the Pleiades — are the only stars that could be identified with reasonable certainty.

- Phase 2: The two horizon arcs were added, in the process covering three stars, of which only one was moved onto the disc.

- Phase 3: A solar barge was added — it plays no role in the astronomical use of the disc.

- Phase 4: The 38 holes were punched into the periphery — probably to fasten the disc to a pole and held upright like a standard. As an astronomical instrument, it would have been held horizontally.

- Phase 5: The one horizontal arc was removed, or lost, during ancient times before it was buried.

Interpretation and Use of the Sky Disc of Nebra

The interpretation of the Sky Disc of Nebra is not totally uncontroversial, and research and academic debates continue on its origin, composition, and meaning, but the museums interpretation currently is more or less as follows:

The disc was used for astronomy and probably for religious purposes too. The two arcs span an angle of 82°, correctly indicating the angle between the positions of sunset and sunrise at the summer and winter solstice at the latitude of the Mittelberg (51°N), where it was discovered in 1999. By using Brocken, the highest peak in the Harz Mountains and visible from Mittelberg, as a reference point, the sunset and sunrise during the summer and winter solstice correspond with the edges of the horizon arcs.

Before the horizon arches were added, the disc was probably used to compensate for the difference in length between the lunar and solar years. The Pleiades play a special role. They disappear from vision in the Mittelberg area during the early bronze age on 10 March next to the new moon and again on 17 October next to the full moon.

The oldest written reference to using the Pleiades to correct the calendar is a millennium younger from a Babylonian text of around the 6th century BC, which stated that an extra month must be added if the Pleiades appear during the spring month before the rise of the new moon.

This may also explain the 32 stars on the disc — 32 days are required from the final month before the Pleiades appear next to the new moon.

The later changes to the disc destroyed this function, as did the interpretation that the disc was later used as a standard on a pole rather than used horizontally. This begs the question if that was done intentionally or whether the original knowledge was lost. The addition of the sun boat — also used by other cultures — hints at a movement away from scientific knowledge.

Around BC 3600, the Sky Disc of Nebra was buried, as an offering together with other items — two bronze swords, two hatchets, a chisel, and fragments of spiral bracelets were recovered from the same pit.

The Himmelscheibe occasionally travels to other major exhibitions but that seems increasingly rare. In such case, one of the very accurate copies are on display.

See also the Sun Chariot in the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen which had the same function as the solar barge and the Golden Hats – a Celtic calendar in the form of a ceremonial hat from around 1000 BC in the Neues Museum in Berlin.

Thematic Exhibitions in the Prehistory Museum Halle

The Sky Disc is on display on the museum’s top floor — turn left at the top stairs but it would be a shame not to follow the chronology of the recommended route to the right. The museum is not very big and even a cursory glance at the main items will be rewarding. Almost all items on display was discovered in or near the present-day state of Saxony-Anhalt.

Mental Power / Geisteskraft

400,000 to 40,000 BC

The exhibition starts with the Palaeolithic (Altsteinzeit / Old Stone Age) and the first roots of humanity in central Europe. The first archaic humans — Homo erectus — moved into central Europe around 370,000. A few implements and skeletal remains are displayed from this period.

A surprise is perhaps the model of a Eurasian elephant in Saxony-Anhalt but the region had a tropical climate before the ice age. An almost complete skeleton of a Eurasian elephant was discovered in 1987 in a coal mine. This elephant died around 125,000 years ago in a lake due to disease but cut marks in the bones and stone knives show that humans utilized the carcass for food and raw materials. More than 1,500 bones from around 70 Eurasian elephants (Elephas antiquus) were discovered at Neumark

In the main hall, many stone implements are on display but these are overshadowed by the huge 200,000-year-old skeleton of the mammoth from Pfännerhall. It was discovered in a local coal mine in 1953.

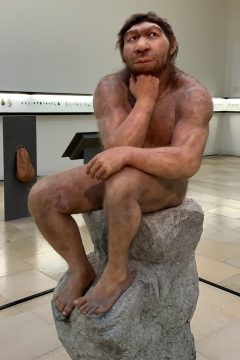

The sculpture of an ancient man is based on archaeological finds of bones and used current anthropological knowledge and criminal identification techniques to produce a model of a human of the changeover phase from Homo erectus to Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. He is deliberately modeled as a thinker — the implements on display in this room show that he certainly used mental power to survive.

Human Succession / Menschenwechsel

40,000 to 5,500 BC

Homo sapiens sapiens entered Europe and a technological revolution occurred. Spears could be thrown to increase the safety distance for the hunter. There is also an increase in the use of jewelry and decorative items and Ice Age Art such as the minuscule female ivory sculptures from Nebra and the scratching of horse heads on stone slabs.

Around 11,500 years ago temperatures in central Europe increased from icy tundra to more or less the current state with forests. For humans, surviving became easier.

The “shaman” of Bad Dürrenberg is the oldest ceremonial grave found in the region. A woman in her late 20s was buried together with a child of 6 to 12 months and a variety of items from many animal species indicating that she must have been a special person.

Living Changes / Lebenswandel

5,500 to 2,800 BC

For more than 99% of human history, humans lived as hunter gatherers but finally in the neolithic era man started to farm resulting in a major change in living conditions. Items from this era include pottery from the corded ware cultures.

Axes and other stone implements to work wood were essential for the new agriculture-based lifestyle, the construction of long houses for living, and to fence in domesticated animals. Wood rarely survives that long but the 3,000 stone axes mounted on the wall (Steinbeilwand) bear testimony of the sudden change to working wood.

As in the rest of Europe, monumental structures for graves were built from around 4,000 BC onwards including dolmens, menhirs, and stone graves. The Rinderbaron (cattle baron) grave from around 3,000 BC does not only show wealth due to the large number of seemingly prime cattle buried in the grave with the man but also placing the 600 kg heavy stone slab onto the roof of the grave certainly required some resources too.

Passion for Bronze / Bronzerausch

2,800 to 1,550 BC

Even without the Sky Disk of Nebra, this section would be a highlight of the museum. The appearance and local working of metal — copper, gold, tin, and bronze — revolutionize life again, as did trade in such items as amber but also more useful items such as salt.

Graves of nobles are often laden with items showing wealth and a clear division between the elite and the ordinary people.

The family graves from Eulau are from this period. In these graves, 13 individuals are buried in pairs or small groups. Some children hold hands with a parent and were positioned face to face. Stone arrow points in the bones of a mother buried with child show that her death was not from natural causes.

The ceremonial burial of the sky disc of Nebra is symbolic of the end of this era

Born in Fire / Glutgeboren

1,550 to 58 BC

The late Bronze to pre-Roman iron age is exhibited one floor lower — utilizing firepower more effectively allows for better weapons but also more agricultural implements.

This is the age of the sword, shields and the lance. Scratches and resharpening showed use while some others were simply status symbols or cultural objects

The end is also increasingly in fire — from around 1300 BC cremation became common. However, still in this period, near Frankleben 200 bronze sickles and 16 axes were buried — not far from where 800 years earlier many stone axes were similarly ceremonially offered, a tradition 30 generations apart.

Iron led to a democratization of metals. At first, like gold only for the elite but knowledge spread fast and soon in every town or village a smith could work the metal.

The beginning of written history in Europe is roughly from 500 BC onwards but in central Germany, the locals remained “barbarians”. Germans were first mentioned by Pseidonios in 80 BC, and famously described in 53 BC by Julius Caesar.

Discovery of the Germans / Die Erfindung der Germanen

The museum currently concludes with a small exhibition of the period of Roman contact with Germany from 58 BC to AD 180 — further expansion to the modern era is planned.

Gold jewelry in the grave from the princess of Profen from the mid-first century and a few Roman luxury items are worth a quick glance but most foreign travelers who made it to Halle had probably already seen better Roman objects elsewhere. This is not totally surprising, as in contrast to traded items, the Romans themselves never made it to Saxony-Anhalt.

Visitors Information for the Museum of Prehistory Halle

The Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte Halle is open Tuesday to Friday from 9:00 to 17:00 and weekends from 10:00 to 18:00.

The museum is closed on Mondays and December 24 and 31.

Admission is €5 for adults, €3 for students, and €2.50 for children 6 to 14. A family ticket is €10.

The audioguide (€2) is worth having for visitors with limited German — not all descriptions are in English.

Transportation to the Prehistory Museum Halle

The Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte, Richard-Wagner-Straße 9, 06114 Halle (Saale), is to the northwest of the city center. It is easiest reached by tram 7, stop “Landesmuseum for Vorgeschichte”, that runs from the main train station via the city center and the late Gothic Marktkirche.

Parking near the museum is very limited. At busy times, use parking lots in the center or the Parkhaus am Bergzoo Halle and continue by tram 7 to the museum.

Halle is a pleasant city with well-rated hotels on Tripadvisor often far cheaper than other larger cities in Germany making it a great option for spending the night before continuing to other destinations. By train, Halle (Saale) Hbf can be reached in around half an hour from Leipzig or Naumburg, and in just over an hour from Berlin on direct trains.

If using only local trains in the region, the Saxony-Anhalt Ticket is a great savings option. This Länderticket covers local train and bus transportation in all of Saxony-Anhalt, Saxony, and Thuringia, and has the same validity and price as the Sachsen or Thuringia Tickets.

More photos on Flickr.